Written by:

Craig O. Cooper, M.S.

Cooper Consulting, LLC

1627 Major Avenue

Riverton, WY 82501

Illustrated by:

Sunrise Engineering, Inc.

47 E. 4th Avenue

Afton, WY 83110

Evan J. Simpson, P.E.

Foreword by Pat Tyrrell

Part I.

Part II.

Part III.

Part IV.

Part V.

Part VI.

REFERENCES

APPENDICES

LIST OF MAPS

Wyoming’s water laws have often been an example to other western states for their ability to keep order in the use of all the varied water supplies within her borders. Although somewhat of a latecomer among the western states to have her water supplies undergo widespread development, Wyoming was a frontrunner in pioneering concepts for the innovative handling of the complex process of bestowing the use of her water to her citizens. From the time of the initial creation in 1868 of the separate western territory now called Wyoming, her streams and rivers have been the lifeblood of her economy and growth. Indeed, the progression of water laws enacted first by territorial legislatures and then by the state legislature for using and allocating her waters can reflect the history and development of the State itself. The names of individuals found on Wyoming water right documents comprise a fascinating “who’s who” of the founding figures in the State’s progress from territorial times to the present.

Water is often looked at as a “free” resource, responsible for man’s continued presence on earth, and consequently the inherent property of every living thing. Still, the history of mankind shows it to be one of the commodities over which wars for its control have been fought. Such contention has engendered, at least in the American west, the vesting of water control and distribution in responsible, neutral and knowledgeable quarters authorized to manipulate its use for the good of all. In Wyoming, that responsibility has been shared by the citizens of the state, through the legislature and offices of territorial and state government, employing, either intentionally or accidentally, many of the greatest water minds in the country.

Numerous individuals are responsible for the existence today of a water use system that meets the present needs of Wyoming residents and provides confidence in adequacy of supplies for the future. In The Conquest of Arid America published in 1899, William E. Smythe, journalist and chairman of the National Irrigation Congress, observed “Wyoming’s place as the [water] lawgiver of the arid region is due neither to geographical location or to superior natural resources; certainly it is not due to large population. It owes its commanding position solely to the character and ability of a few public men who happen to have found in this line of work their best opportunity for usefulness.” That comment is just as prudent today, over 100 years after its writing, as the list of those “few public men” has lengthened with the passage of time.

Documentation of the historic work of these individuals is carefully protected in various locations, and for a completely thorough investigation of their contributions to Wyoming’s water history, there is no substitute for study of those documents in their entirety. Dozens of reports, articles, collections, pamphlets, and other writings have been prepared through the years, addressing various issues and aspects of water use in terms of contemporary thought and evolution of the laws. Such concepts as “appropriation,” “duty of water,” “beneficial use,” “adjudication,” “surplus,” and others have been discussed and revisited regularly in Wyoming’s history, and can only really be understood today when recognized in their historic context. An understanding of the sequence of development of the State’s water laws and the context of the political climate in which they were enacted can often provide a background for why things are done the way they are done today. It is the intent of this presentation to provide assistance for that understanding in a single location and in a chronological and understandable format. To attempt to remain chronologically pure, many events are referenced more than once; the first time when the concept first appears in Wyoming history and then again at later times when it resurfaces. For example, the Wyoming v. Colorado lawsuit was first filed in the Supreme Court in 1911, but a decree was not entered until 1922. That suit is first mentioned in the part of this history discussing the 1911 time period, but results of the court decree are not discussed until the discussion of events in the 1920s. Thus, if a topic of interest seems slighted in its first mention, the reader is encouraged to read on, as the additional information will likely be found in the time period in which further activity on that topic occurred in history.

Four topics were found to have more history than would fit the format of the remaining text, and, to allow them full discussion, were placed in separate appendices at the end of the document. The mention of those topics at various locations in the text generally contains a reference to the appendices either parenthetically or by footnote.

Summaries of the laws explained herein come from the texts of the statutes themselves as annotated and revised through the years, hopefully paraphrased accurately for briefer versions of sometimes complicated language. Not every mention of water in every legislative session in Wyoming’s history is addressed, as some machinations of the legislature provide little more than necessary housekeeping of concepts already included. Nonetheless, a conscious attempt has been made to include in adequate detail all the salient concepts from which water administration and use today have evolved.

General historic Wyoming background referenced herein is derived primarily from the extensive published history of the exceptionally authoritative Dr. T. A. Larson. Dr. Larson’s History of Wyoming is properly recognized as the definitive history of all aspects of the growth of the present state from prehistoric times, and is required reading for placing events in the history of Wyoming water in their full political context. Similarly, the histories of C. G. Coutant, Frances Birkhead Beard, Velma Linford, and Bill Bragg all provide insight into conditions in Wyoming at any chosen historic time, and were drawn upon for that background. However, for a progression of water-related events through the history of the State in one- and two-year increments, there is no chronicle equal to the Reports of the Territorial and State Engineers. The knowledge, foresight, and professionalism of each of those individuals and the agency they commanded as exhibited through their reports is incredible. Those reports were relied on heavily in preparation of this text, but they also contain countless other historic facts of importance not included here because of time and space limitations, but which must be consulted for a full understanding of the history of that critical office.

In attempting to describe the important concepts that resulted from the various water lawsuits in Wyoming’s history, it is critical to recognize that the one- or two-sentence summaries of those cases included herein capture in no way the complex entirety of those contests. The brief descriptions of those cases are taken primarily from Wyoming Digest summaries and from the text of the cases themselves. The complete texts of the pertinent court opinions provide backgrounds, peculiar facts, and rationale for the decisions rendered, and must be consulted for the full understanding of any case discussed. Similarly, the records and decisions of the State Engineer and Board of Control in matters that have come before those historic bodies are available in their offices and should be consulted for a more full understanding of any of their actions referenced in this history.

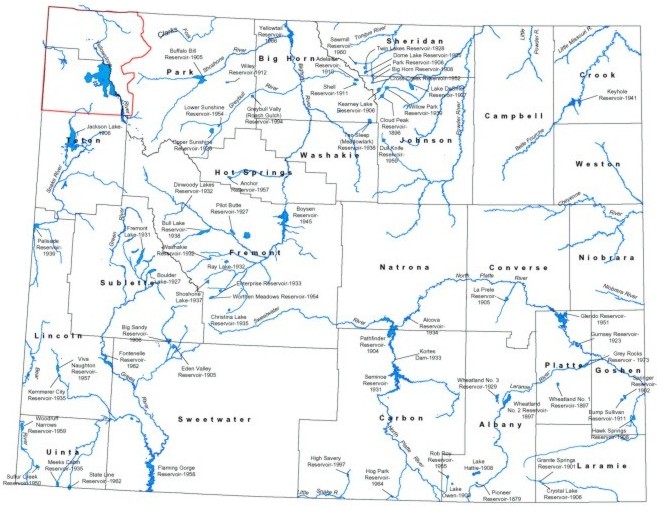

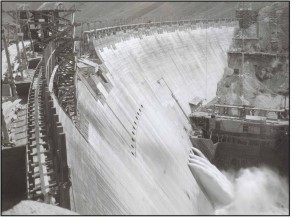

Other information in this history is gleaned from various published and unpublished sources, the State Archives, Wyoming State Library, State Engineer’s Library, the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center, Wyoming Water Development Commission materials, water rights documents, permits, certificates, orders and tabulation books, and from the author having served on the State Board of Control for 21 years. A list of pertinent documents, files, etc., most of which were read, studied or consulted for preparation of this history, is included. The photos are all courtesy of the University of Wyoming American Heritage Center, the Wyoming State Archives, the Wyoming State Museum, and Loren Jost at the Riverton Museum in Riverton. The map of Significant Reservoirs and the dates they were permitted and/or built is courtesy of Catherine Cooper. The preparation of this history was requested by the Wyoming Water Development Commission as part of the Snake/Salt River Basin Planning process for Water Division Four and includes the period from 1868 to 2002.

When I started as Wyoming State Engineer in January of 2001, it did not take very long to realize that Craig Cooper knew the history of Wyoming water law very, very well. At that time, he was the senior member of the Board of Control, having attended his first Board meeting as Superintendent of Water Division III in January of 1981. If you do the math, this means Craig sat as a deliberative member of that body for 87 quarterly meetings before his retirement after the third quarterly meeting in 2002. If you do more math, that amounts to over 30 percent of all the Board of Control meetings ever held up to his departure. Perhaps only Mr. L. C. Bishop, who was first Superintendent of Water Division I for 16 years, and then served as State Engineer for 18 years, and Mr. John Teichert in Division IV who served for 30 years, have a longer Board of Control tenure in all of Wyoming history. Craig sat on the Board 10 years longer than Elwood Mead served as Wyoming Territorial and State Engineer combined.

In my comparatively short tenure presiding over Board of Control meetings, one thing is clear: these meetings offer more of the richest debates and thorough descriptions of our water laws than any other venue. Often, I’ve said (only partly joking) that I learn more about Wyoming water laws during those week-long quarterly meetings than in the two and three-quarters months in between. It was in this environment, where the Board deliberates on its issues in a setting permeated with law, practice, interpretation, ideological arguments, and history that Craig was in his element. During his tenure, the State of Wyoming saw water battles associated with Nebraska v. Wyoming lawsuits, the Big Horn General Adjudication, energy development, struggles with and ultimate passage of our instream flow statutes, and numerous other important water topics. There likely was no paragraph in all of Title 41 that wasn’t cussed and discussed during his years. To put this all in a nutshell, there are few people better equipped to write the history you are about to read.

Experience is one thing, desire is another. Craig’s love and respect for the history of our water administration system (which really is a history of Wyoming’s development and evolution, if you think about it) runs deep. He is not only knowledgeable about Wyoming’s water history, but is pretty salty when it comes to our history in general. Ask him about the Johnson County cattle war, Tom Horn, or the fur trade, and you’ll see what I mean. In other words, the history herein is multi-dimensional and was written by an individual who really wanted to do it and do it right. It is a reflection of the author’s own love of his home state and his willingness to not just read a statute or a court case but delve into its history and reason for being. The facts are sprinkled lightly with personal observations, which serve to set them in historical or practical context without editorializing. It is a long overdue piece of work, and any person with an interest in Wyoming’s water will find it indispensable.

Pat Tyrrell, Wyoming State Engineer

May, 2004

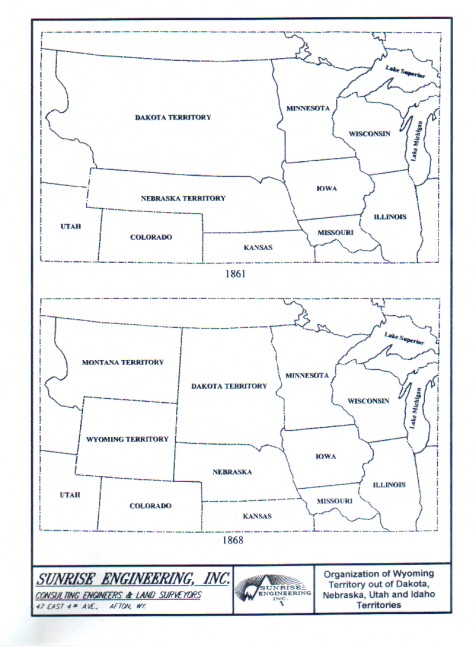

On July 25, 1868 the Territory of Wyoming was created by the U.S. Congress partitioning off a 110,000 square mile rectangle at the southwestern edge of the huge Dakota Territory, together with some land segregated out of Nebraska, Idaho and Utah territories (see Map 1). The new Wyoming Territory was said to be rich in gold, silver, copper, iron, coal and pasture, and it was different enough in vegetative aspect, and the farmers in the eastern part of Dakota Territory had little enough in common with it, that they believed it a good idea to sever it from Dakota’s political jurisdiction. The Wyoming population of 8,014 citizens was primarily distributed in the boom towns of Cheyenne, Laramie City, Rawlins Springs, Green River, Rock Springs and Evanston, along the nearly-completed transcontinental railroad, with army forts, telegraph stations, and mining fields across the territory holding a smattering of residents as well. A few squatters under the Pre-Emption Act of 1841, the Mining Act of July 26, 1866 and the Homestead Act of 1868 also lived out along some of the streams of the territory. The Shoshone Indian Reservation, established by treaty signed three weeks earlier on July 3, 1868 at Fort Bridger, was located near the center of Wyoming Territory.

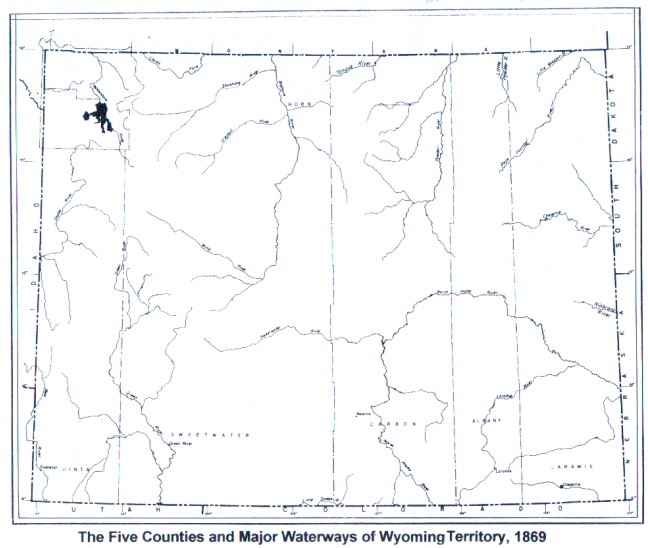

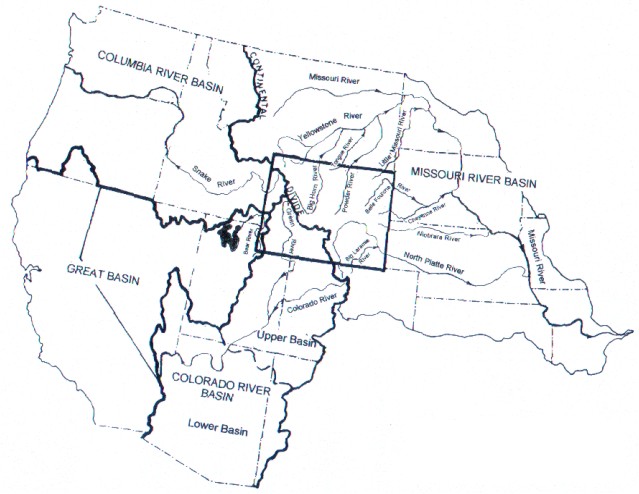

Upon their arrival, early citizens of the new territory found a network of streams and rivers carrying life-giving water in all directions off the mountains that formed the continental divide—a divide which separated the waters of the territory into separate river basins contributing ultimately to the oceans on both the east and west coasts of North America. The headwater streams and rivers tumbled rapidly out of the steep terrain of the Wyoming high country and then slowed to meandering green-vegetated threads across the vast brown and yellow open flats of the prairies and plains. Most already had names, courtesy of the Indians, fur trappers and explorers who had been using them for years. The Platte River, Laramie’s Fork, Powder River, Green River, Stinking River, Clark’s Fork, Big Horn, Little Big Horn, Popo Azia, Sweetwater, Big Sandy, Fontenelle Creek, LaBarge Creek, Wind River, Snake River and dozens of other names were already found to be in common and recognized use at the time the territory was established. The organization of five counties by late 1869 (see Map 2) created a county government political system with district courts and county officials to conduct the local business and maintain order among the tide of immigrants.

Delegates from all parts of the territory gathered in Cheyenne as the first Wyoming Territorial Legislature on October 12, 1869, and, as part of that assembly, Wyoming’s first water laws were drafted. Early settlers were present in the territory mostly as a result of federal land disposal acts, and the territorial government considered water to be attendant to the land disposed, and its ownership, therefore, to not necessarily be under territorial jurisdiction. Under the Mining Act of July 26, 1866, Congress had recognized the right of settlers to possess water rights by prior appropriation on federal lands, and recognized their ditch and canal rights-of-way across unoccupied federal lands as vested for serving water to settled lands. Early Wyoming government thus refrained from enacting restrictive encumbrances on a Wyoming citizen’s inherent right to appropriate and use the waters of the territory.

The water laws that came out of that first legislature dealt exclusively with the recognition of a need to direct water appropriators as to considerations in the construction of ditches for taking water out of the streams and rivers of the territory. There was no proscription in those laws, or for many years after, as to amounts of water allowed for the various uses, or as to any specific procedure for getting permission to build a ditch, or any definition of what uses were recognized as legitimate. Nor was there any identification or appointment of authority figures to oversee or monitor water use. Free river (unregulated) conditions existed universally across the Territory. The recognition was that one who wanted or needed to use water out of Wyoming’s streams was free to build a ditch and begin diverting—to appropriate—without notice or oversight. If three or more persons chose to associate for the purpose of building a ditch to serve the needs of each of them, however, they were required to file a certificate of incorporation with territorial officials describing various details about the line (size and path) of the ditch and its stream source. This requirement appears to have been more for keeping records on Wyoming corporations than for anything to do with water.

The considerations imposed on the sparse population of water users by those first territorial laws were that a ditch builder could not direct the water of any stream from its original channel to the detriment of anyone who had a “priority of right,” and that there must “at all times be left sufficient water for the use of miners and agriculturists who may have a prior right to such water along said stream.” Additionally, ditch owners were required to keep their ditches in good condition so that water could not escape the ditch to the injury of any party, and anyone who damaged or interfered with any of the facilities of a ditch company could be convicted in any court of competent jurisdiction.

Thus the rudiments of a sound water rights system were recognized and taking shape, particularly the recognition of the value of priority of appropriation, and the necessity for stewardship of appropriated1 water. Those two concepts have never been out of favor since that first legislation and both continue to be cornerstones of the system yet today. The 1869 laws were a specific rejection of the concepts of riparian water law, which in its simplest form, is a system of water allocation entitling only those individuals living along the banks of a stream a right to make use of the stream. A key distinction of that doctrine is that the right of the streamside landowner exists whether or not the water is used, i.e. no showing of beneficial use is required for the right to be retained.

By the early 1870’s, the open-range cattle business had distributed a human population to all parts of the Territory of Wyoming. The U.S. government offered free grass and the unpatented range was relatively uninterrupted from border to border. Thousands, and then hundreds of thousands, of cattle ranged unconfined across the territory, drifting constantly to new grass and ahead of the weather, with their caretakers selecting strategic home ranch settlements on the streams and rivers. Numerous private ditches had been constructed, and more were constantly being constructed to irrigate small acreages of creek-bottom pasture and native hayland to enhance feed production for small confined herds of cattle and horses, and to provide domestic water and raise garden produce for the homesteads popping up along those drainages. Gristmills were showing up on streams in the more populated areas of the territory, and towns were beginning to use water for municipal purposes. Sluice mining operations and the powerful railroads were also making prominent use of territorial water. Except for the parcels continually being specifically privatized by the various federal land disposal acts, the U.S. Government claimed ownership of the unoccupied land in the territory.

The 1875 Territorial Legislature enacted the first legislation actually described as an Irrigation Act, and although it consisted of only three pages of statutes, additional concepts still embodied in the law today were included. Section 8 of those statutes, for example, regarding the obligation of ditch owners to maintain their embankments, is still found word-for-word in W.S. 41-5-101 of today’s statutes, 127 years later. Similarly, the language of Section 12, regarding the bridging of ditches crossing public roads, is unchanged in today’s version found in W.S. 41-5-104. All persons living in the neighborhood of a stream were entitled to appropriate irrigation water “to the full extent of the soil,” inferring perhaps the first reference to the well-recognized concept of beneficial use in allowing the soil to accept all the water it could hold but maybe no more.

One important part of those 1876 laws that has since disappeared was a provision in Section 2 entitling a person not living along the stream to a right-of-way for ditch construction through the property of the landowner(s) between him and the stream. Numerous ditches were built in Wyoming while that right-of-way provision was in effect, and the loss of that provision may be the root of difficulties between neighboring landowners today in disputes over the historic locations of some of those ditches.

The other provision of note in those 1876 laws was the first ever attempt at empowering selected individuals with the authority to apportion water in times of scarcity among different localities along a given stream where the volume was not sufficient “to supply the continual wants of the entire country through which it passes.” It is noteworthy that assigning a specific diversion amount to the users was carefully avoided, and that these precursors to the present office of water commissioner were to apportion the available water on a rotational basis, rather than by priority date or amount appropriated. Embodied in the 1876 laws was the philosophy of the Territory of Wyoming that her streams were to necessarily provide water “for the continual wants of the entire country” through which they passed, and it was only when the volume of water in a stream could not do so that these “commissioners” were to take action to rotate the supply.

Although the bulk of irrigation across the territory was being accomplished by small private ditches or ditch companies, in the late 1870’s the first large-scale canal project, the Pioneer Canal out of the Big Laramie River, was instituted by the Pioneer Canal Company. That project included the first use of a reservoir, the Pioneer Reservoir built in 1879, as a necessary component of the irrigation development. In 1883 several of the well-known territorial cattlemen, including Joseph Carey, Horace Plunkett, William Irvine, and Francis E. Warren, organized as the Wyoming Development Company and began construction of a second sizable irrigation project out of the same river system, the Wyoming Development Company Canal at the Wheatland Colony.

By 1886, the Territory of Wyoming had 17 years of independent government under its belt and was focusing on seeking statehood. Its population stood near 50,000 people, around half of which were still in the towns along the Union Pacific railroad, with the other half scattered about the remainder of the state, mostly in connection with the powerful open range cattle industry, mines and military outposts. Large ranches controlling thousands of acres and employing dozens of cowboys supported the small towns springing up in all parts of the territory. Since 1880, approximately 4,850 claims for private acquisition of federal lands in Wyoming had been filed under the Pre-Emption Act of 1841, Homestead Act of 1868, Timber Culture Act of 1873, and Desert Land Act of 1877, and more were being filed. To obtain a patent under these acts required, among other things, occupation of the lands and some use of water from the streams to prove habitation.

The irrigation laws grew from twelve statutes in 1876 to 30 statutes in 1886 and a comprehensive territorial water code was taking shape. The 1886 session laws contained several new provisions, including statutory designation of eight areas called “irrigation districts,” with a corresponding provision for appointment of a water commissioner in each district to attempt to keep order over increasing water use. Appendix B discusses at length the water commissioner system that developed from this provision.

Water commissioners were appointed for two-year terms by the territorial governor on recommendation of the county commissioners. Although obligated to be constantly on standby, the law provided that they “shall not begin their work until they shall be called on . . . by application in writing.” When called to work, the commissioners’ duty was to “divide the water of the natural stream or streams of their districts among the ditches taking water . . . according to the prior rights of each . . .” but they “shall not continue performing services after the necessity therefore shall cease.” A statute providing penalties for willfully interfering with the settings made by the water commissioners also first appears in the 1886 laws, and these laws exist in substantially the same form today.

The term, “beneficial purposes” first shows up in the 1886 laws as well, in the context of being a label for acceptable uses for which appropriation and adjudication of water might be made, but not as a basis, measure or limit of a water right. Use of the term may have been intended to give the territorial courts a measure by which to deny an appropriation if such was found desirable for whatever reason.

Although there was no standard rate of water duty2 or individual allotment yet employed, further legislation was enacted which obligated the water commissioners to “prevent unnecessary waste of water” in their districts. The law allowed the water commissioners to manipulate headgates to deliver no more water than was required and would be used for the purposes of the appropriation. Thus, beneficial purpose and priority date were the only restrictions on the water an appropriator could divert. In other words, the water commissioners, when called to work, were not required to measure specific amounts of water out to the appropriators, but were instead to use the relative priority dates to deliver whatever amount of water could be used without unnecessary waste.

Unfortunately for the water commissioners, no tabulations of those relative priority dates had yet been prepared, and the only way to establish them was prescribed by another new provision in the law. Section 10 of the 1886 laws required all appropriators claiming water in the territory to file a statement of claim to their ditch and appropriation with the local district court by September of 1886, which was within six months of the passage of the act. Those claim statements were to include, among other things, the capacity of the ditch, an amount of water claimed, and the “date of appropriation of water by original construction.” Then, Section 15 invited those persons who desired a determination of priorities of the rights in the various ditches and ownerships on their streams, to petition the district court for a decree establishing them. The court decree was required to fix the priority date of each appropriation and “identify the amount of water which shall be held to have been appropriated.” This amount was to be determined using ditch dimensions and capacity and from testimony of the appropriator. Unappropriated water was declared to be property of the public.

The 1886 Act was the first time Wyoming law provided recognition that her water use system would necessarily have to be based not only on priority date of an appropriation, but also on a fixed amount of water that would be recognized and recorded as attaching to that particular use. Still, the law was reluctant to fix that amount universally as a function of government, and was instead content to accept and record the word of the individual appropriators as the guide for how much water had been appropriated. Those amounts obviously varied from ditch to ditch and area to area based on information provided in claims submitted.

It was also the first time that written notice was required to show intent to appropriate. Section 13 of the 1886 laws required that thereafter, every person intending to appropriate must file a statement with the county clerk, and from the time of filing any such statement, that water would be deemed to be appropriated. This notice requirement paved the way for the later cornerstone of Wyoming law found in the filing of an application for permit to appropriate with the State Engineer. It was now clear that water users in Wyoming were going to have to get used to paperwork. However, the act of allowing the appropriator to make a statement defining his own appropriation in terms of ditch capacity, at a time when water measurement and knowledge of water amounts were little understood, invited difficulty in the ensuing court decrees.

Provision was also made in the 1886 laws to use the beds of streams as carriers for reservoir water previously appropriated, making “due allowance for evaporation and seepage” in delivery of that water, as determined by the water commissioner. This provision continues to be present in the law today. Reservoir construction was prohibited “in or across the channel of any natural or running stream,” i.e. off-channel reservoirs were the only ones authorized by law. Reservoir owners were also made liable for any damage created by their reservoirs.

Additional 1886 legislation required the installation of fish barriers at the diversion points of ditches to keep fish out of ditches, and prohibited water users from allowing any part of their water or wastewater to “overflow . . . or damage any established road or highway.” Both of these provisions are still present in similar statutes yet today. Also enacted was a requirement that county surveyors make accurate measurements of and record the carrying capacities of every ditch in their county, filing a certificate attesting to the same with the Territorial Court, “as prima facie evidence of the carrying capacity of the ditch.” Another portion of a law enacted in 1886 established a preferred or superior status for municipal water, stating “. . . no priority of water right shall take from any city or town the water required for the use of the residents thereof.” This single exemption from strict adherence to chronological priority dates lasted in the law only a few years, and is the only time in the history of Wyoming surface water rights that any one use could eclipse priority dates of other uses, until the decreeing of reserved water rights for the Wind River Indian Reservation in 1988.

In 1887, the unrepealed Compiled Laws and Session Laws from all previous years were reorganized into new titles, chapters and sections and published as Revised Statutes of Wyoming. Little substantive change was made at this time to the comprehensive and ambitious water legislation that came out of the 1886 session, and it seems apparent those 1886 provisions pertaining to water, particularly the requirement for recording claims and securing court decrees allocating water rights, were still in the process of being fully implemented in the distant offices of the county clerks.

The disastrous winter of 1886-87 was still raging at the time the legislature met, thus its effect on the water laws and the irrigation practices of territorial citizens was yet unrecognized. Wind, bitter cold, and incessant accumulation of snow that winter killed thousands of unprotected cattle, forever changing the open-range cattle business, and being responsible in part for a new approach to irrigation in Wyoming. Reuben Mullins, in his Recollections of a Cowboy on the Wyoming Range, 1884-1889, suggested that particular winter revealed to any cattleman whose herd wasn’t devastated to the extent of bankruptcy, and who had enough capital left to continue in the business, that irrigating forage to produce winter feed would now have to be a critical part of a successful cattle business. Such a revelation generated a much keener interest in water rights and land patents among cattlemen than had previously been expressed, and claim statements took on a more urgent and serious importance, some to the extent that it has been suggested they may have had a part in such matters as the lynching of Jim Averell and Ella (Cattle Kate) Watson a year and a half later in 1889 (see Sweetwater Sunset by Daniel Y. Meschter).

The tenth legislative assembly in early 1888 acted on the growing need for appointment of a territorial official with singular and consummate authority over use of the territorial waters. Drawing on past experiences in neighboring Colorado and adopting a bill proposed by J. A. Johnston of Wheatland, the 1888 legislature created the first office of Territorial Engineer, a position to be held by an individual “known to have such theoretical knowledge and practical skill and experience, as shall fit him for the position.” The Territorial Engineer was to be appointed by the governor and serve for a term of two years. One of his duties was, for the first time, to have supervision over the work of the county water commissioners.

Previous legislation, particularly the 1886 requirement for filing statements of claim to water and then having the district court adjudicate the priorities and amounts for those claims, was found to be creating situations on certain streams in which some citizens were favored with water and others were injured. Primarily due to district court judges’ lack of knowledge about water volumes and measuring techniques, the court decrees often bestowed outrageous water volumes to the claimants who appeared, so that in some cases only one or two ditches on a stream were authorized to take all the water the stream could generate. Those volumes were invariably in excess of what the appropriator could place to beneficial use, so that his neighbors found good reason to seek redress. The 1888 legislature was aware of this mischief, and passed Representative Johnston’s bill aimed at bringing professional engineering expertise to the administration of territorial waters.

The statutes that accompanied the one creating the office of Territorial Engineer required an ambitious and unenviable set of tasks for the new engineer to accomplish. Reportedly, there were around 3,000 individual ditches diverting water from streams across the territory, only a handful of which had been adjudicated through the court process established in 1886. The 1888 statutes required the Territorial Engineer first to secure careful measurements, in cubic feet per second (cfs), of the flows of each stream in the territory from which water was taken for irrigation. Secondly, he was required to measure ditches when so requested, and provide the party making the request a certificate of the size and carrying capacity of the ditch measured. The law required that the information in these certificates then be filed in the office of the Territorial Engineer and received in all the territorial courts as “prima facie evidence of the facts therein set forth” as a tool to assist in more realistic court decrees.

Although there was still no uniform water volume assigned to appropriations established by the claim process, the 1888 statutes were the first to fix the cubic foot per second (cfs) as the legal standard of measurement for the territory. They were also first to require an appropriator to install a measuring device “at or as near the head of his ditch as is practicable” to assist the water commissioner in delivery of water to the respective priorities on the stream. To give the water commissioner some guidance as to how much water to allow through the measuring devices, the statutes fixed a limit on water appropriations as “so much thereof as may be necessarily used and appropriated for irrigation or other beneficial purposes, irrespective of the carrying capacity of the ditch,” and any amount in the ditch greater than that was to be considered unappropriated water and be returned to the stream source. This provision contributed to disagreement in the upcoming Constitutional Convention over the definition of the word “appropriated.”

The 1888 laws also contained the first admonition for appropriators to continually place their water to beneficial purposes or risk such negligence being interpreted as abandonment after two years of non-use. It was also the first time the term “surplus water” appeared in Wyoming law, such water being described as water in a ditch which was surplus to an appropriator’s needs. The statutes did not prohibit surplus water from being in a ditch, but prescribed instructions as to how the appropriator could furnish that water to other landowners “at reasonable rates.”

Expanding on the concept of preferred use first implemented in the 1886 laws, the 1888 laws identified domestic use as being able to preferentially supersede earlier priority dates for all other uses during times of water shortage, and agriculture uses to be preferred to manufacturing uses. Additionally, Wyoming’s first environmental water laws were part of the 1888 enactments, being fairly detailed and comprehensive directives aimed at allowing fish unobstructed passage up and down the streams and rivers of the territory, and keeping them out of irrigation systems, as well as prohibiting pollutants from being introduced into the “waters of any such fish.”

In March of 1888, right after the close of the legislative session, Territorial Governor Thomas Moonlight appointed Elwood Mead, a professor at Colorado Agricultural College in Fort Collins, as Wyoming’s first Territorial Engineer.

By mid-1889 the Territory of Wyoming was working hard to soon be included as one of the United States and by September was ready to hold a Constitutional Convention for the purpose of creating a State Constitution to propose to the U.S. Congress. That assembly convened in Cheyenne on September 2nd, and adjourned on September 30, 1889 with a State Constitution drafted to propose to Congress for ratification. Territorial Engineer Mead, a few months over a year in office, provided the delegates to the convention with abundant information regarding the condition of irrigation and water use in Wyoming and was in a position to propose improvements in the existing water laws based on his observation of how such laws had been found to be working in his tenure. The Journal and Debates of that convention provides absolutely fascinating reading as to the discussions leading to the water references ultimately included in the State Constitution.

The Convention assigned irrigation and water matters to “Committee Number 8,” composed of seven delegates from across the territory, to prepare such provisions as were deemed worthy of constitutional inclusion, and that committee spent much of the month of September in that duty. In the end, although numerous issues were considered during the deliberations of the committee, only eight provisions were considered to be of such consequence that they deserved inclusion in the State Constitution, with the idea that the other important issues could be instituted statutorily by the legislature. The included provisions were placed within Article 1—DECLARATION OF RIGHTS, Article 8— IRRIGATION AND WATER RIGHTS, and Article 13—MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS and read as follows:

“Article I—DECLARATION OF RIGHTS

Article VIII—IRRIGATION AND WATER RIGHTS

Article XIII—MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS

These cornerstone provisions encompassed the results of days of debate, and left for upcoming state legislative action the details of implementing their terms in day-to-day water administration.

The State Constitution that grew out of the landmark convention was ratified by the people of the territory at the general election on November 5, 1889, and became effective with the Act of Admission to the Union in Congress, eight months later on July 10, 1890. Dr. T. A. Larson, discussing the admission to statehood and adoption of the constitution in his History of Wyoming, states “What little originality there is in Wyoming’s constitution is mainly concentrated in Article VIII (Irrigation and Water Rights),” a comment that reinforces the common and widespread understanding that Wyoming’s water laws were innovative, timely, and prepared to meet the prospect of western growth.

The territorial legislature met one more time in early 1890, continuing the direction it had started through the years of territorial government, but realizing that with statehood imminent, a new state legislature would soon meet and possibly completely revise the direction those territorial laws had taken. Certain concepts in the law were being seriously questioned by some citizens while other citizens girded to fight for the historic manner of water use with which they had become comfortable. The 1890 territorial session created an act authorizing cities and towns to provide a system of waterworks for their residents, specifying such matters as how to finance such works, how to acquire water rights, etc. It also revisited the fish provisions spelled out in 1888, and redescribed the eight “irrigation districts” into a new total of nine such districts being oriented much more along county boundary lines than originally drawn. The new irrigation district descriptions corresponded more closely to district court jurisdictional boundaries to supposedly allow better success in preparation of court adjudication of the water rights awaiting such action. In retrospect, they need not have bothered with this amendment (in fact, would have been better off without it), as the state legislature, meeting for the first time ten months later, removed adjudication duties from the courts and vested them in the newly-created Board of Control. Appendix C details how unique and functional and in all manner good, the transfer of this duty to a body equipped to deal with it on a full time basis came to be.

Map 1. Organization of Wyoming Territory, 1868

Map 2. The Five Counties and Major Waterways of Wyoming Territory, 1868

Four months after the close of the 1890 territorial legislature, on July 10, 1890, Wyoming terminated her political status as a territory, and, by the Act of Admission, became the State of Wyoming. Her constitution had been ratified by Wyoming popular vote in the last November general election, and now by the U.S. Congress, and its provisions went immediately into effect. The governor went about appointing the Territorial Engineer, Elwood Mead, into the office of State Engineer and he began the exhaustive work of perfecting the premier water use system that he prosecuted diligently for the next 8½ years.3

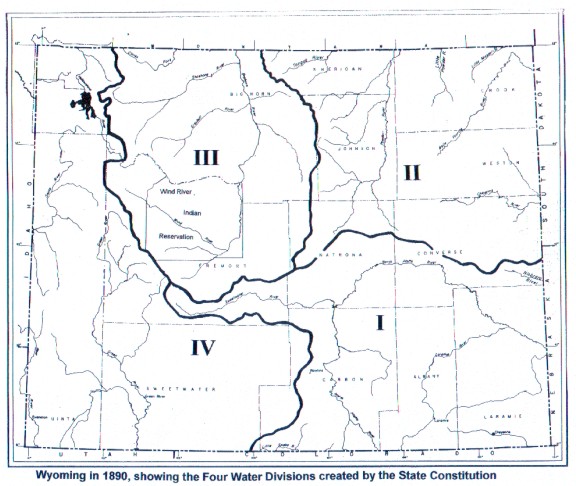

The first Wyoming State Legislature convened late in the year, and by December 22, 1890, had drafted and approved the first State water laws. Those laws started out by creating provisions to enact and comply with the constitutional requirements to divide the state into four water divisions and have appointed a superintendent for each division. While the most recent territorial laws were heavily drawn upon for their value as the last step in the evolution of territorial water law, there were new provisions in the new laws, some based on the ambitious on-the-ground experimentation done by Engineer Mead in the previous two years. Other provisions just clarified some of the concepts in the existing law, and the result was a clean and readable fifteen-page act combining the acceptable attributes of the past thirty years of trial and error in the use of Wyoming’s streams with the emerging science of irrigation.

Water Divisions

Map 3. The Four Water Divisions Created by the Wyoming Constitution

Division Superintendents

Also according to the Constitution, the four Superintendents, along with the State Engineer as President, would comprise the State Board of Control. In that capacity they were statutorily required to meet twice a year, specifically starting their meetings on the second Wednesday of March and the first Wednesday of August. The superintendents of the four water divisions sat together with the State Engineer as the State Board of Control for the first time in March of 1891, and one of their items of business was to comply with the new statute directing them to divide the State into water commissioner districts. These commissioner districts replaced in both concept and area the old “irrigation districts” created under territorial law. As the district courts were now removed from the initial water rights adjudication process, the necessity for having water administration boundaries line up with district court jurisdiction boundaries disappeared as well. Instead, the new water commissioner district boundaries could be drainage basin-oriented, so that a single water administration official could generally have authority over all the water rights on an entire stream from its headwaters to its mouth. Since the water commissioners were county employees, however, an exception still existed in some locations where the stream crossed from one county into another (see also Appendix B).

Section 14 of chapter 8 of those first state statutes gave the superintendents the duty to execute the laws relative to the distribution of water, and Section 15 gave each the authority to “make such other regulations to secure the equal and fair distribution of water . . . as may, in his judgment, be needed . . .” as long as those regulations weren’t in violation of any other Wyoming law. Anyone who considered himself injured by the action of a superintendent could appeal such action to the State Engineer for suspension, amendment, or confirmation of “the order complained of.” Those statutes, duties and authorities remain relatively unchanged in today’s law and are carried out regularly.

Board of Control; Adjudication

A process outlining exactly how the adjudication process was to be completed was well spelled out in the 1890-91 law. It consisted of several steps, beginning with a public notice to appropriators on the selected stream that on a specified future date, the State Engineer would begin measuring the stream and the ditches diverting from it. The notice also specified a date when the superintendent would begin taking testimony from appropriators as to their claims to water, and provided a form (now called a “proof”) for the appropriators to fill out. That form, completed under oath, was to state the nature of the use, the dates the survey of the facility began, the date commencement of construction began, the date completion of construction occurred, and the date when water was first used. If for irrigation, the acreage of land irrigated was required as well.

On the specified date, the superintendent then took the completed form and any additional testimony from any respondents who appeared at the appointed time and place to advance their claim. When that was finished, he issued notice of a date when all the pertinent evidence of water right claims on that drainage would be held open for public inspection, to afford anyone claiming an interest in the stream the opportunity to refute or protest any appropriator’s claim. If a protest was lodged, the superintendent was required to hold an additional hearing to collect evidence on that matter. Whether protested or not, at the completion of this information-gathering phase, the superintendent transmitted all the evidence and testimony to the state office of the Board of Control in Cheyenne to be processed for inclusion on the agenda for the next meeting, when he, his fellow superintendents, and the State Engineer would deliberate the evidence and issue an order determining priorities.

Concurrent with this activity by the superintendent, the State Engineer or his assistants were required to examine the same stream, its diversion works, ditches, irrigated lands, and lands susceptible to irrigation, and prepare a plat map of the stream showing these features. This map and information was also made available to the Board of Control as additional evidence for completing the adjudication of prior water rights on the stream.

The next step in the process was for the Board of Control to enter an order determining and establishing the priorities, amounts and descriptions of the water rights adjudicated, based partly on the “amount of water which shall have been applied for beneficial purposes.” In fixing the amount that the appropriator could take from the stream, the law required that the appropriator “shall at no time be entitled to the use of more water than he can make a beneficial application of on the land.” Based on the historic practice of free river use, the amount of water used beneficially varied from time to time and place to place. In fixing the amount of water that the Board of Control could allot by certificate to the appropriator for equal footing and regulation purposes, it provided that “no allotment shall exceed one cubic foot per second for each seventy acres of land for which said appropriation shall be made.”4 (Later court cases clarified that “beneficial use” and the one cfs per 70 acres certificate allotment are not necessarily the same thing). By dividing the total acreage approved in the certificate by 70, the Board of Control then determined the cfs allotment to be entered on each order. These “order records” were meticulously completed and preserved in secure volumes in the office of the Board of Control, and, together with the plat maps, are still accessible and used today for the same purposes as when they were first issued.

The final step in awarding individual water rights to appropriators who had made claims was the issuance of a certificate of appropriation, recording all the attributes of that particular claim which had been adjudicated by the Board of Control. The certificate was entered into the “certificate records” of the Board of Control, with a duplicate transmitted to the county clerk of the county in which the water right existed, who, following recordation in county records, forwarded the certificate to the appropriator. The statutes also provided for an appeal process to the district court if a party felt aggrieved by the Board of Control adjudication, and a requirement that the court advance any such appeal to the head of its docket and give it precedence.

Tabulation of Adjudicated Rights

Permit Process

The permit process began with filling out an application form with all pertinent information about the proposed new use, and filing it with the State Engineer. Upon receipt of the application in his office, the State Engineer was to diligently record the date and time of its receipt. That critical recordation time became the priority date of the new water right—the date which would forever mark that water right’s place on the list of competing priorities for that stream. All water rights on that stream with earlier priority dates would have a better right, and all those that came to be permitted after that date would always be junior in their right to take water from the same stream. Applications were accepted for original supplies for all water uses employed in the State, for reservoir construction, and for enlargements of existing facilities. Recognizing that some projects would take years to complete, the State adopted the “doctrine of relation back” under which the priority date of water rights attached to project lands would all relate back to the date the permit application was received in the office of the State Engineer. Even if it took 50 years before the first water was applied to beneficial use on part of the project lands, as long as the project as a whole was being completed with due diligence, the priority date of water applied to newly cultivated land would relate back to the original priority date that the permit application was accepted by the State Engineer.

The permit application also asked the permittee to advise the State Engineer as to the times required to commence construction, complete construction, and place the water to beneficial use. Upon examination of the completed application, if the State Engineer found it to be in compliance with the law, found there to be unappropriated water in the named source of supply, and found the application not to be detrimental to the public welfare or public interests, he endorsed it as approved, and authorized the applicant to proceed with the proposed water development. If any of those conditions were not met, he had the authority to refuse the application, modify it for less water, or grant a shorter time period for perfection of the appropriation. The statutes required the applicant to also file a plat map of the proposed facilities, which would perpetually remain on record in the State Engineer’s Office for reference as to the physical intent and attributes of the appropriation. Those maps continue to be an indispensable resource in water right study yet today. The statutes gave the Board of Control the duty to hear appeals from anyone who felt aggrieved by a permit endorsement of the State Engineer.

Implicit in the permit process was the concept that the “terms of the permit” were inviolable; i.e. when an applicant asked for the right to do a certain thing with the State’s water, the State Engineer granted only what the applicant asked for, no more and no less. An applicant who asked for the right to make a certain use of water at a certain place was bound by the terms of the permitted use and would be in violation of his permit if he attempted to make a different use than permitted, or at a different location than permitted. This condition continues to be rigidly adhered to in water right permitting today.

Upon completion of the construction and application of water to the permitted beneficial use, the permittee notified the State Engineer, and the adjudication process began with the filing of a proof as described above, following the same process on through to issuance of a certificate.

Other 1891 laws included a special legislative appropriation for the State’s first stream gaging station to be constructed under Elwood Mead’s direction on Clear Creek near Buffalo in Johnson County, and an Act concerning “fast driving over county bridges.” The latter Act provided that “no one shall drive or ride over a county bridge faster than a walk,” and authorized the county commissioners to put up a sign using those words at each end of any county bridge. Speeders convicted were susceptible to a $10 fine or imprisonment for “not less than ten nor more than thirty days,” or both.

The comprehensiveness of the 1890-91 statutes demonstrate the extensive thought and consideration given to creating a solid process for making the transition from a territory to a responsible state of the union. The statutes enacted by that first state legislature established a body of water laws that have remained essentially the same in the years between then and today, although regular modifications to that body continue to keep the law modern and flexible to meet changing times in Wyoming.

After the monumental water legislation events of the first years of statehood, attention turned to using and carrying out the enacted laws. With a sound organization in place to provide order, intensified effort was made to bring the vast irrigable acreage across the state into agricultural production. Reports were that millions of acres lay out in the State waiting for irrigation water, while the rivers of the state flowed on. In T. A. Larson’s

words, “Governor William A. Richards told the 1895 legislature of ‘this vast wealth of land and water lying idle, side by side, awaiting only the magic touch of labor and capital, intelligently combined, to be coined into wealth.’”

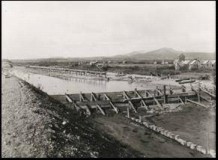

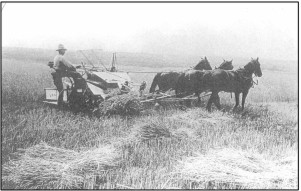

Up to this point, the ditches in Wyoming were small, short, and stayed within the narrow flood plains of the stream and river valleys, irrigating relatively small acreages in the bottomlands. Horse pastures, cow pastures, gardens, orchards, mill races, stockwater troughs through corrals, and small crop fields were served by hand-built ditches hugging the bottoms of the first-level terraces following the meander of the streams downhill. To cultivate the higher elevation bench lands further from the water sources would require construction and reclamation efforts on a massive scale, and similar securing of finances, but state officials saw prosperity in the promise and embarked on the journey with fervor.

The 1894 Carey Act

The major accomplishment of the 1895 legislature in respect to the water laws was to prescribe procedures for implementing the Carey Act to irrigable lands across the State. The federal act gave the states ten years to irrigate and reclaim the lands proposed for development, and Wyoming promptly set about promulgating its rules, giving the state Board of Land Commissioners the duty to select, manage and dispose of the land. Persons, companies or organizations wishing to take advantage of the act were to file an application with the State Board of Land Commissioners for the land, and with the State Engineer for the water rights to irrigate it. It was expected that moneyed interests would associate to provide the capital necessary to undertake the large construction projects, and form development companies which would then contract with the settlers for delivery of water to the lands selected for segregation. Lands proposed by the State for disposal from the federal government were essentially patented (segregated) to the State, became “state lands” in the context of local disposal, and then further sold on contract to the homesteaders, who were generally under contract with their respective development company for providing a water supply.

In a move that was atypical for a state that had placed so much recognition on the proprietary right of a landowner to appropriate his own water right, the legislature provided that development companies who could build canals under the provisions of the Carey Act could become water right “brokers” for the settlers intending to locate within a Carey Act project. Potential settlers could then contract with the development company to buy “perpetual water rights” for the land they reclaimed, which would also entitle them to a proportionate interest in the canal and other irrigation works of the delivery system. They would pay the State around 50 cents an acre for the land, and the development company somewhere in the neighborhood of $20 an acre for the water rights. The development company would then issue a “water right deed” as proof the deal was complete.

No sooner than the guidelines and requirements were in place, an organization called the Shoshone Irrigation Company in August of 1895 filed for water rights and applied for the first Carey Act project in Wyoming, the Cody Canal, to divert from the South Fork of the Shoshone River upstream from the Town of Cody. In December of 1896, the Big Horn Basin Development Company filed for Carey Act application to the Bench Canal Project out of the Greybull River upstream from the Town of Burlington. On the Laramie River, the Wyoming Development Company continued toward completion of its project with construction of Wheatland No. 1 Reservoir in 1897 and Wheatland No. 2 Reservoir in 1898. In 1900, the Big Horn Basin Colonization Company made Carey Act application to develop considerable acreage under what they called the Sidon Canal, diverting from the Shoshone River near the Town of Lovell. And in 1902, following the success of their Bench Canal Project, the Big Horn Basin Development Company filed again for Carey Act support of a new project they called the Wiley Canal, to take water out of the South Fork of the Shoshone River several miles upstream from the diversion point of the Cody Canal.

By the time the legislature met in 1899, it was known that the State of Wyoming’s water laws, as thoughtful and well-intentioned as they were, were not going to go unchallenged in the courts. At least three lawsuits between competing appropriators had occurred in the decade of the 1890’s and, while the law had stood the test, it was clear that the legislators hadn’t thought of everything in their statutory enactments. The first lawsuit, Frank v. Hicks, had occurred in 1893 as a contest to determine whether a Wyoming water right, and the ditch to carry it, passed in a conveyance of the realty even if there was no mention of the ditch in the transaction. The Wyoming Supreme Court determined that, since it was accepted in Wyoming that water rights attach to the land rather than the ditch or landowner, they indeed pass with the realty, even without mention. The second case, also in 1893, entitled McPhail v. Forney, discussed the importance of providing for a means of conveying water to a tract with water rights. The third, Moyer v. Preston, decided in 1896, clarified exactly what was, and what was not, an “appropriation” in Wyoming. In that case, the court adopted the prevailing philosophy that certain elements were necessary to identify a water use as an appropriation—an intent to appropriate, physical demonstration of the intent to divert with reasonable diligence, and application within a reasonable time to a beneficial use. That case also documented a specific rejection of the doctrine of riparian rights in Wyoming.

Although it was not a Wyoming court case, Howell v. Graham, first decided in 1894 in Montana federal district court, involved a Wyoming homesteader who had appropriated water from Sage Creek in 1890, and a Montana homesteader who had appropriated upstream on the same creek in 1893. Immediately upon possession of his homestead, the junior Montana appropriator (Graham) diverted the waters of Sage Creek to the extent that not enough water came across the state line into Wyoming for the senior Howell appropriation. The Wyoming appropriator complained in federal district court in Montana and, based on the doctrine of prior appropriation, was decreed a “prior” right, with damages assessed against the Montana junior appropriator. Although he won the case, Howell was back in the same court two years later in 1896 with evidence that Graham was violating the decree by depriving Howell of water altogether. This time, the Montana appropriator was found guilty of contempt and fined. A year later, another suit was filed with the same results, and yet another with the same results in 1903. The junior Montana appropriator knew that Wyoming water administrators had no jurisdiction across the state line in Montana, and that Montana officials would not take water from its own appropriators to send to Wyoming, and he thus continued to irrigate his crops while the lawsuits accumulated.

By 1903, a neighboring senior Wyoming appropriator and another junior Montana appropriator had joined the fray. Morris v. Bean was a continuation of the same lawsuit on Sage Creek, and resulted in the same judgment from the federal district court. Appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, the prior judgments that priority dates must be honored across state lines were upheld and the Montana appropriators ordered to send the water to Wyoming. Still unconvinced after five judgments against them, the Montana appropriators, in Bean v. Morris, appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court which, in 1911, upheld the lower court decrees. To this day, over 90 years and a Supreme Court decree later, the State of Montana has never honored or delivered water to the downstream senior Wyoming water right on Sage Creek.

The 1899 legislature reiterated the 1887 duty of the water commissioners to regulate headgates to prevent waste of water, and reinforced their duty to divide the waters of the streams according to relative priority, closing headgates when necessary in times of water scarcity. They continued to have the power of arrest and the authority to employ suitable assistants when necessary that had been given them by the 1890 state laws.

The 1888 provision requiring the county commissioners to establish rates for the sale of surplus water was still in effect in the 1899 laws, as was the 1887 provision for the entitlement of a ditch right of way through the lands of any owner or owners whose lands lay between the stream and the fields of a landowner needing access to that stream. Those provisions have since disappeared.

Partnership ditches also received attention in the 1899 statutes. The law provided for the district court, upon request of the ditch users, to appoint a “suitable person” to take charge of any partnership ditch in which there was disagreement over division or distribution of water, whose duty it would be to make a proper distribution of the water among the co-users of that ditch. Although water commissioners were in place over much of the State, their jurisdiction to divide the waters was restricted to headgates out of stream sources, and they were prohibited from entering within the boundaries of ditch companies or partnerships to divide water between or among co-owners of such ditch. The new law regarding partnership ditches also provided a lien mechanism for recovery of costs when one or more co-owners failed to do their proportionate share of the maintenance necessary for the proper upkeep of the ditch. This law continues to be an important provision in the operation of joint-user ditches today.

Also, although the requirement that reservoirs all had to be constructed off-channel was no longer in the law (opening the way for the widespread dam construction on-channel as well as off), the liability of reservoir owners for any damages caused by their reservoirs continued to be paramount to owning a reservoir.

The close of the 19th century saw Wyoming as a state full of promise, with considerable historic irrigation in place, a premier system of water administration in operation (thanks to Elwood Mead), and with extensive irrigation projects and their attendant economic development on the horizon statewide.

The period between 1899 and 1907 saw tremendous development activity in the State (the 1900 census showed 92,531 residents), with a commensurate growth in the statutory guidance over water development. The 1901 legislature enacted provisions for permitting the industry of floating railroad ties and logs on the streams and rivers of the State, requiring that such activity be done with the least interference or injury to any irrigating ditch existing along that stream. Two years later, the 1903 legislature gave attention to statutory guidance for construction of reservoirs, as it was apparent that the success of all the large private, Carey Act, and later, Reclamation Act, canal projects would be dependent to varying degrees on spring runoff waters being caught and stored in reservoirs for late season water supply. Those statutes, and their 1907 expanded versions, specified the procedures for securing reservoir permits, and required the filing of what were called secondary permits to describe the uses and places of use to which the reservoir water in the primary (reservoir) permit would attach. Adjudication of the secondary permit would occur when beneficial use of the water stored in the reservoir was proven.

By 1900, the annual pattern of runoff in Wyoming’s streams was well-recognized by developers and settlers. In an area of slight rainfall, as compared to humid states from to which many settlers had come, Wyoming's natural water supply depended (and continues to depend) almost entirely on snowpack during the winter months. While the mountains accumulated water in the form of snow between the months of October and April, the growing season months of May through September received only slight natural moisture--nowhere near enough to mature crops without irrigation. Additionally, the climate pattern consisted of rapidly warming temperatures in May and June, usually to the extent that the snowpack all melted and ran off in those months. The snowmelt filled the streams and rivers to overflowing for that short period of time, raced down the channels and was gone, leaving a relative trickle in most locations by early August.

As successful crop production requires adequate water all through the growing season into late August and September, the need was great for a way to catch and hold some of those flood flows so they could be parceled out at a later date when natural moisture and streamflows were minimal. The construction of reservoirs fulfilled that need. By directing substantial amounts of those rushing flood flows into a holding basin, water could instantly be saved from downstream loss, and later made available by operating the outlet gates to release stored water back to the channel at times when the natural flow was not able to meet the needs downstream.

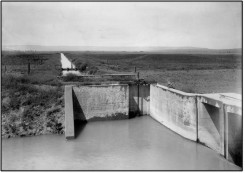

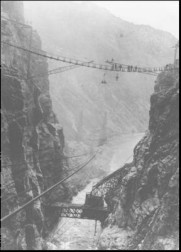

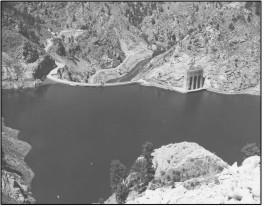

The early 1900’s saw reservoir-building activity all over the State (see Map 4). In Water Division One, Lake Owen Reservoir was permitted in 1900, Granite Reservoir in 1901, Pathfinder Reservoir in 1904, LaPrele Reservoir in 1905, Crystal Reservoir in 1906, Lake Hattie and Hawk Springs Reservoirs in 1908, and Bump Sullivan Reservoir in 1911. In Water Division Two, Dome Lake received its permit in 1905, Kearney Lake Reservoir in 1906, Lake DeSmet in 1907, and Big Horn and Park Reservoirs in 1908. In Water Division Three, Okie Reservoir had been authorized in 1895, and Newton Reservoir in 1898, Paint Creek Reservoir in 1902, Luce Reservoir in 1905, Shoshone (Buffalo Bill) Reservoir in 1905, Blake-Denton Reservoir in 1906, Wales Reservoir in 1908, the Lost Cabin Waterworks Reservoirs in 1908, Thompson No. 1 Reservoir in 1909, Adelaide Reservoir in 1910, and Shell Reservoir in 1911. In Water Division Four, Church Buttes Reservoir was permitted in 1901, Erickson Reservoir in 1902, New Fork Lake in 1903, Eden Reservoir in 1905, and Eden No.2 (Big Sandy) Reservoir, Jackson Lake Dam and Elkhorn Reservoir in 1906. These facilities, and many others, have provided the State with untold benefits in numerous ways in the 100 years since their construction, and are testaments to the Shoshone Dam 1908 foresight of the settlers who built them, or had them built. They provide water for all beneficial uses recognized in the State, and provide considerable flexibility both in time and amount as to how Wyoming’s water supplies are used for the benefit of all her citizens. While use of water from those reservoirs is specifically tied to the uses described in their permits, and the ownership of the storage is tied to those appropriators who expended the capital to have them built, there can be no argument that in an arid state, the ability of those reservoirs to manipulate the runoff period has been of inestimable value to all citizens.

Carey Act

Reclamation Act of 1902

Within a short time, several stalled Carey Act projects were converted to Reclamation Service projects and revitalized under federal funding. In Wyoming, the first of those was the project of the Cody and Salisbury Canal Company, which became the Shoshone project in 1904; second was the North Platte Canal and Colonization Company project in 1905; and the third Reclamation Service project was the dam at Jackson Lake in 1906.

The 1905 Act (Second McLaughlin Agreement)

The State Engineer in 1906 accepted bids from interested land development companies for construction of canals and reservoirs for the relinquished, or “ceded,” lands so that the homesteads being concurrently filed with the U.S. Land Commissioner could be irrigated. The contract was ultimately awarded to a group of Chicago investors, the Wyoming Central Irrigation Company, and that company immediately filed for state water rights for around 330,000 acres, portions of which would eventually be irrigated by the Wyoming Number 2 (Riverton Valley) canal, the LeClair-Riverton Number 2 canal, and the Wyoming (Midvale) canal. Also filed on as part of the project were a number of reservoirs on various upper Wind River tributaries, with anticipated and permitted storage volumes totaling some 326,000 acre feet. Although it was not originally a Carey Act project, financial difficulties within Wyoming Central Irrigation Company a few years later led to congressional approval for Carey Act application to the Midvale portion of the project by 1910. However, the project never did proceed under that approval.

Irrigation Districts

Following the legislation, irrigation districts were formed in all parts of the State, and new ones are still being formed today under the historic provisions of the 1907 laws as amended through the years. Lands within the State’s irrigation districts are today among the most desirable country properties because of the equitable district structure as a public water distributor.

The 1907 laws also spelled out detailed procedures for condemnation of public ways of necessity for “reservoirs, drains, flumes, ditches, canals, or electric power transmission lines on or across the lands of others for agricultural, mining, milling, domestic, electric power transmission, municipal, or sanitary purposes.”

Water Administration

The statutory period that tolled water rights abandonment for non-use was extended from two years to five years in the 1907 laws, and the 1888 and 1899 statute that recognized any ditch as a common carrier, when it carried surplus water for furnishing to users other than the recognized ditchowner(s), was retained. The 1907 laws also, for the first time, made it a misdemeanor to take water without a permit, and provided that “possession or use of water” without such a permit would “be prima facie evidence of the guilt of the person using it.” This enforcement provision remains in the law, and is a deterrent to unauthorized diversion yet today, although the present penalty is regarded by water administration officials as inadequate.

The other substantial change to a historic statute was the elimination of the requirement that measuring devices be “as near the head of such ditch as is practicable,” substituting instead a provision that measuring devices now be installed “at such points along such ditch as may be necessary for the purpose of assisting the water commissioner in determining the amount of water that is to be diverted into such ditch from the stream, or taken from it by the various users.” Such a modification from the original language appears to be in response to Elwood Mead’s desire stated in 1903 (Irrigation Institutions) for “the establishment of an approximate standard duty of water when measured at the heads of canals,” while at his job with the USDA in Washington D.C.

Between 1900 and 1910 another handful of water lawsuits were decided in the Wyoming Supreme Court. Farm Investment Company v. Carpenter in 1900, established that an appropriation is complete upon the diversion of water and its application to a beneficial use, and that the State Board of Control, as an administrative rather than a judicial body, has the supervisory powers for appropriation, distribution, and diversion of the State’s waters. Another, Whalon v. North Platte Canal and Colonization Company, decided in 1902, clarified that the priority of a water right dates from the filing of the application in the office of the State Engineer, rather than from the dates of the survey and/or partial construction of the ditch, and that a ditch built without authority obtains no rights.

In Stoner v. Mau, decided in 1903, the court held that when one enlarges another’s ditch, he does not obtain any right to the water of the original appropriator, and instead, must appropriate his own water and is bound by any internal contract he makes with the original owner as to relative ownership of the ditch. Another 1903 case, Willey v. Decker, dealt with the diversion of water in Montana into a ditch that crossed the State line into Wyoming and the ramifications of such “interstate” problems. Justice Charles Potter observed, in talking about that case a year later, “In my opinion, it will eventually be found necessary to resort to compacts between the interested State governments” to remedy such cases. That case also clarified that the public’s right in water must recognize, and is subject to, the right of appropriation.

In still another 1903 case, Ladd v. Redle, the Court held that an appropriator has the right to work in the stream channel even on the lands of his neighbor to do what is necessary to get the water to flow to his headgate as long as he doesn’t injure any other appropriator. The concept of a “futile call” was litigated in 1904 in the case of Ryan v. Tutty where the court required that junior rights on tributaries must be regulated for a calling senior on the mainstem, unless it can be shown that the water taken from the junior, because of channel loss, will not reach and benefit the senior. That case also clarified that the actions of water commissioners and superintendents are executive and not judicial.

Although territorial and early State law implied that a valid appropriation was tied to a specific point of diversion from the stream, in 1904 the court in Johnston v. Little Horse Creek Irrigating Company, found there was nothing in the law to prevent a change in the point of diversion if it could be accomplished without injury to other appropriators. Additionally, the court found that an agreement between two appropriators to alternate the use of their water (rotate) was acceptable as long as no other appropriator was injured thereby, and that an appropriator is entitled by his water rights only to the amount of water he can beneficially use. All of these concepts later were incorporated into statutory law.

In 1905, the court determined that the owner of a ditch would be found liable for damages caused to another party by negligence or unskillfulness in construction of his ditch, (Howell v. Big Horn Colonization Company). And in 1906, in Mau v. Stoner, the court required that when one appropriator contends that a water administrator is in collusion with another appropriator, the burden is on the complainant to prove his allegation.

Although it was not a Wyoming case, a 1908 Colorado case had implications for Wyoming as well. In Windsor Reservoir and Canal Company v. Lake Supply Ditch Company, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that a reservoir owner had the right to fill his reservoir from the permitted source of supply only once during any given year. Although Wyoming didn’t have a judicial declaration that the same “rule” applied in Wyoming until the 1970 case of Wheatland Irrigation District v. Pioneer Canal Company, the Wyoming Board of Control subsequently recognized that “one-fill” rule in its rules and regulations.

The 1909 legislature, in continuing to refine and perfect its system of statutory water law, defined that “beneficial use shall be the basis, the measure, and the limit of the right to use water at all times,” and provided the first definition of a water right and its attributes in the following language: